The not-quite-romance of Eudora Welty and Ross MacDonald.

Some friendships hover between romantic and platonic, anchored to the latter by circumstance or fate. It’s a sitcom trope: the will-they-or-won’t-they couple, always teetering at the edge of love. But though TV demands a tidy resolution—the answer is almost always that they will, and do—in life such friendships often remain in limbo indefinitely, stretching on for years, even decades.

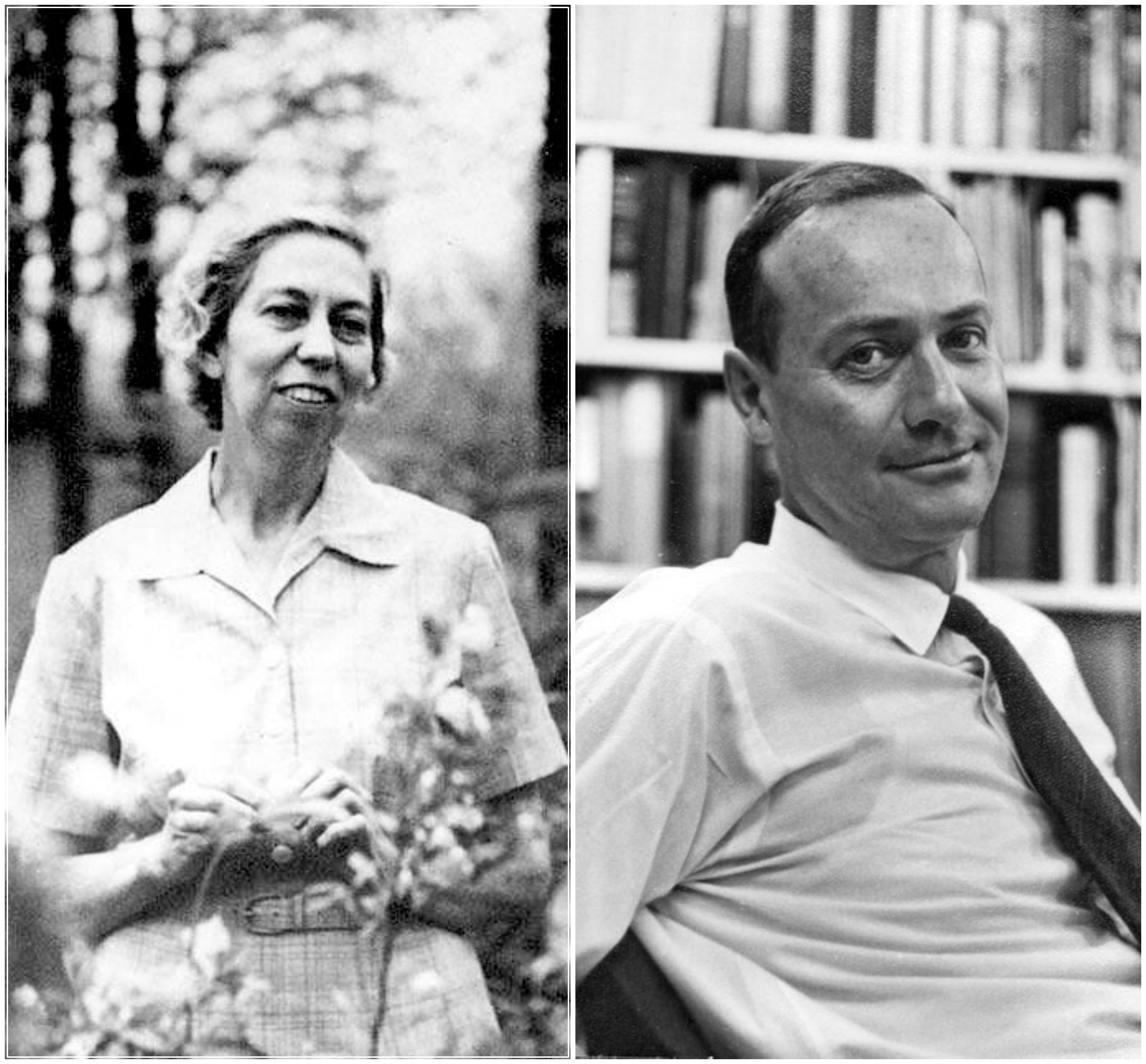

Such was the case for Eudora Welty and Ross Macdonald. By the time they became acquainted, in 1970, both were well established in their fields—Welty in that nebulous genre called Southern literature, and Macdonald in hard-boiled detective fiction. Welty’s stories and novels captured the voice of small towns in Mississippi; Macdonald, the pen name for Ken Millar, set his novels in Southern California, where he and his wife, Margaret, had settled. His books explored, through his Philip Marlowe–equivalent Lew Archer, the ways in which the dream of suburbia could turn twisted and nightmarish.

Welty was an avid reader of crime fiction, so much so that the now-defunct Choctaw Books in Jackson used to keep a pile of paperbacks on hand for when she stopped by. Though she went on to win a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award, the only award Welty publicly displayed in her house was the Mystery Writers of America’s Raven Award, which she received in 1985 for being the Reader of the Year. She and Millar, by all accounts, had admired each other’s writing from afar for many years, but never connected. Then Welty published her novel Losing Battles, and Millar, using his real name, wrote her a brief, appreciative note.

“This is my first fan letter,” Millar wrote. “If you write another book like Losing Battles, it will not be my last.” Indeed, it wasn’t close to being his last. With the ice broken, Welty and Millar struck up an epistolary friendship that endured until his death in 1983, exchanging some 345 letters. Even after the onset of Alzheimer’s disease left Millar unable to reply, Welty wrote him. To read their correspondence, collected this summer in the excellent Meanwhile There Are Letters by Welty’s biographer Suzanne Marrs and Millar’s biographer Tom Nolan, is to eavesdrop on a long, nuanced conversation about literature, politics—“Oh God! I had to meet Pres. Nixon!” Welty wrote—and the victories and frustrations of life as a writer. Both wrote voluminously about birds, exchanging the number of grackles, pigeons, and golden eagles spotted in their gardens. It reads as a long-running private joke, or even a coded language. Millar, to Welty: “3,000 cranes were standing in the water of Soda Lake. A thousand took to the air as we were watching, flew over us in long lines bending unbroken like lines of music then burst into actual music, a gleeful melodious grumbling … ” And from Welty to Millar, a limerick: “A condor who couldn’t call quits/was giving the bird-watchers fits—simply besotted/with being spotted/he booked himself in at the Ritz.”

They exchanged books, cards, and Christmas cake, often crossing letters in the mail in their eagerness to respond. Millar gave solace to Welty when some close friends of hers died: “Like the trees in your yard,” he wrote, “we lose limbs but still put out new leaves.” When they were traveling, the pair would sometimes send notes in advance to each other’s destination, thus remaining in touch even away from home.

Can it come as any surprise, then, that these letters occasionally read like the prelude to a courtship? Though cautious throughout—both Millar and Welty make frequent reference to Millar’s wife, as if reminding themselves not to get too carried away—an unmistakable adulation animates their exchange. Welty, after all, was a prolific correspondent, maintaining epistolary conversations with many of her friends, but the tenor of her writings to Millar is different. “Our friendship blesses my life, and I wish life could be longer for it,” she wrote. After one letter in which Welty had accepted Millar’s request to dedicate a book to her, he wrote that he “abandoned myself to indulgence and simply sat and read your letter over several times with tears in my eyes. It was one of the great moments of my life.” In another, Miller professes that “your letters came as part of this general spring feelings. It gives me an occasion to tell you how much I loved Losing Battles and love its author.” And then, tacked on in the usual guarded way: “As does Margaret.”

Millar’s marriage, according to Nolan and Marrs, was rocky, particularly after the death of the couple’s only daughter. Margaret’s voice, of course, is left out of the conversation, so it’s difficult to know what she thought of her husband’s deep relationship with Welty. Early in her correspondence with Millar, Welty attempted to strike up a similar exchange with Margaret, as she had with her editor William Maxwell and his wife, Emily. (Those letters are collected in the equally excellent What There Is to Say We Have Said.) But her entreaties didn’t seem to work, for whatever reason, and so Margaret Millar remains, however unfairly, more an obstacle than a character in the story of Welty and Macdonald.

As for Welty, she was in her midsixties by the time she got Millar’s first letter, and had never married. The love affair of her youth, with an apprentice writer John Robinson, had ended when it came to light that Robinson was living with another man in Italy. (Welty remained friendly with him afterward.) In lieu of having children or settling down, Welty traveled extensively, worked intensely, and maintained a coterie of devoted friends; after the death of her brother, she also cared for her nieces.

So the sitcom question remains at the heart of these letters: Did they or didn’t they? Welty and Millar met in person only on a handful of occasions. The year after Millar sent his fan note, he waited to meet her in the lobby at the Algonquin Hotel, tipped off by colleagues that Welty was staying there. They spent an evening walking the streets of Manhattan, apparently enraptured with each other’s presence. All told, through writer’s conferences and the occasional visit, Welty and Millar spent fewer than six weeks in each other’s company—not a long while, on one hand, but more than long enough, on the other. Trying to read between the lines of their correspondence can feel strained and a tad gossipy, leading to fervent speculation in the realm of fan fiction.

Still, the idea of such a literary power couple is irresistible to imagine. Sure, some of it is just pure curiosity, the tabloid detective work we all occasionally engage in with cultural figures. At least for me, it’s also because the idea of a covert cross-country tryst would help shatter the myth of Welty as a Southern spinster, sour and fusty, cooped up with her flowers and her typewriter. Welty, like Flannery O’Connor and Harper Lee, is all too often shunted into that category. When literary men choose to stick to their small town environs, they are regarded as noble and solitary. When women do, they are too often painted as recluses, dried-up and sheltered, passionless.

At its deepest level, investment in the did-they-or-didn’t-they of the situation reflects the intimacy between these writers and their audience. The letters remove Macdonald and Welty from the realm of abstraction, the stuff of stamps and textbooks, and present them as people you’d like to have at a dinner party: bright, funny, warm, and full of silliness. Reading the correspondence between Millar and Welty, you almost begin thinking of them as your friends—friends who should get together, already. And if they did, who knows? The letters may be littered with clues. After all, both writers enjoyed a good mystery.

Margaret Eby’s South Toward Home: Travels in Southern Literature is out now.